(this post originally appeared on designingsound.org)

Let’s consider (for the next 178 words) the production process as a river, and we are a drop of water flowing from the beginning of the project to the end. Like every other drop of water, we have a goal: to make it to the end of the river. And as a single drop of water, there are numerous challenges we face as we hurtle down the river, many of which are the result of our own shortsightedness, creative struggles, or management of just getting from point A to point B. There are also a great many issues we face and obstacles we must overcome, originating from outside of our own control. Rocks, sticks, dams, and eddies which may block or slow the flow of water, much the same way interdepartmental communication, decoding feedback, and managing milestone expectations may hamper audio development. To bolster this admittedly weak simile, I decided to ask a handful of successful, talented audio leads throughout the video game industry about some of the challenges they constantly face and ways they have gone about mitigating their harm to the audio of a project.

As we’ll see, many problems are unsurprisingly similar across studios and thus give us a space where we can collectively attempt to improve the industry and thus improve our own sanity and defuse some of the unnecessary challenges we face day to day. Before diving into these issues we all face, let’s first meet the people who were kind enough (and had time in their schedules) to succumb to an interview:

- Jaclyn Shumate, Audio Director, PopCap

- Jason Kanter, Audio Lead, Avalanche Studios

- Kenny Young, Freelance Audio Director, Composer & Sound Designer at AudBod.com

- Rob Bridgett, Audio Director, Eidos Montreal

Interdepartmental communication

Communication, especially between departments, is often a source of breakdown in a project no matter the field. Successful projects are often ones where the goals are crisp and the lines of communication are known, understood and utilized frequently. This is not to say that a project cannot be successful without clear communication, but it becomes exponentially more difficult. Regardless of how successful communication may be, pitfalls are inevitable.

Communication “always fails in one way or another, ” says Rob Bridgett, ” Every team and situation responds differently and every situation is slightly different, and it has to fail before it can be fixed.” He finds that one-on-one communication (with other leads) is crucial and has both scheduled and unscheduled time allotted to catch up with other leads and ensure they are on the same page. A diverse range of communication tools from instant messaging to face-to-face communication (either in person or via Skype) is crucial because, “email communication always fails at some point because it is abused as a communication method. I’ve found it is only useful when used as a small, formal part of an overall communication strategy of other methods.”

For Jaclyn Shumate, and indeed for all of us, “cultivating communication…is one of the most important jobs of an audio person.” Similar to Rob Bridgett, she will “always check in with individuals on the team, and see what they are working on, instead of relying on production tools – or lockout deadlines.” It’s this face-to-face time and constant discussion that helps raise awareness of audio within other departments.

After being locked out from a build on the director’s whim while he was still completing his work, Kenny Young, realized “that quality was my responsibility and wasn’t going to come from anyone else, and that communication isn’t a one way street – you need to second-guess and confirm crucial information, especially at crucial times on a project.” This second-guessing is the same reason Rob Bridgett and Jaclyn Shumate set up their one-on-one time to try and mitigate these issues or at least confirm suspicions about content changes and course direction.

In one instance, Jason Kanter had the misfortune of working on a project where the duties were explicitly divided into programming on one coast of the U.S. and creative content (art, design, audio, etc.) on the other. There was little to no face-to-face interactions between these disparate departments across multiple time zones. The setup proved so contentious that each studio blamed the other for all issues throughout the production from frame rate drops to broken tools. This created a toxic environment that eventually led to the project’s cancellation. Kanter ruminates, “that if the entire team were in the same location, there’s a chance the game may have seen the light of day.” And that is another important aspect of communication: it’s not solely about information dissemination, but also about building rapport and friendship. On this specific project, “there was no collective camaraderie. No sense of family,” and when we think about our most successful teams or projects they often involve a level of intimacy and kinship that are an intangible element of great work.

Since communication is never perfect, Shumate also has other tools at her disposal to help catch non-communicated changes. RJ Mattingly, technical sound designer at PopCap, “made a sweet script that sends us an email every time someone makes a change that affects audio. This means we will get an email if someone deletes an animation timing event, or an audio script attached to a prefab.” In a perfect world we don’t need tools like this, but we also need to be proactive. While we are fostering better communication, we must also try to prevent information from slipping through the cracks through whatever means we have available.

Communication is a tough nut to crack. The lessons here are Always Be Communicating, but having contingencies for communication failure are still important. The more you can connect with individuals, the more successful your communication will be, but the responsibility to get the information we need to do our jobs and ensure content is not changing in the eleventh hour lies with us.

Decoding feedback

Another issue heavily related to communication is that of taking feedback and translating it into something your team can understand and iterate upon. Sound is an art form and, like any art, trying to quantify it into written or spoken language often proves illusive. Furthermore, most people outside of the audio community may not understand (or properly use) audio terms and technologies or be able to communicate with the same language we use daily. Therefore our challenge becomes multi-dimensional: we must acts as interpreters and translators while ensuring we understand what the desired result is before we embark on translating feedback into action.

Kenny Young told me of a time when he was doing a review of a cinematic with his team and immediately heard exactly where and how the audio was not supporting the movie. The interesting thing to him was that, “each of them had picked an aspect of something they had heard in that moment, and because the moment wasn’t working, ascribed the problem to the thing that they had heard, not because it was actually the problem but simply because that is what they had heard.” While this is an issue we have all dealt with, Young went further and did some research as to why and how this happens. Through his research he found that, “people retrospectively ascribe justification for their feelings all the time . . . (and) . . . if you just dismiss people as ignorant (because what they say is ignorant), you overlook the gift they are giving you. When someone has a bad experience, that isn’t questionable, ever – that was their reality. So when someone says something is specifically wrong with the audio, and you know what they are saying isn’t true, ask questions which get to the root of how the experience made them feel and try to reverse engineer the cause.”

Rob Bridgett has a very direct way of dealing with feedback which ties directly into the way he handles interdepartment communication. He will always prepare at least three variations of a sound for anyone he is collaborating with. “We listen through each one and discuss. I say up front I am going to play three versions so I can set expectations. This gives the other person some different elements to react to and points us in a direction.” For him decoding feedback is made easier by being a moderator to the feedback as the creative leads are delivering it.

And how about the other side of the equation? While so much of our job is spent having to translate feedback from leads, what about when we need to encode our own feedback into a language which our audio team can understand? Jason Kanter faced this issue and called it his, “most challenging feedback experience.” To provide his designers with the greatest amount of creative freedom he tried to couch his feedback in abstract terms; not as abstract as “more ‘purple’ in a gunshot but maybe asking for it to sound a little less ‘wooly.’” The results were less than stellar and led to frustration both on the sound designers part and for Jason whenever he needed to provide feedback. His solution was actually quite simple, and only works because he is dealing with people who speak a common language. He figured out to, “simply tell them exactly what was wrong with the sound design on a more technical level. I’d usually start with a slightly abstract description of the issue but then follow it with suggested technical solutions. ‘This impact is too biting. Try attenuating some 3-5Khz.’ or ‘That gunshot sounds a little too hollow. Maybe try reducing the mid-distance gunfire layer and using some more close perspective.’ Altering my approach in how I communicate made all the difference in the world. In the end it greatly improved their work as well as our relationship.”

Another interesting dilemma is when your vision does not mesh with a creative director’s idea of what something should sound like. For Jaclyn Shumate, the “biggest challenges have come when I have disagreed with the creative direction, but have had to follow it.” But she took a potentially stressful, creatively draining situation and turned it into a strong lesson in design. “It can be hard to ‘hear’ a sound before it is created when it is not what you would choose to make! So, I asked very specific questions to try to understand what the lead had in their head. I didn’t like the final result, but it wasn’t bad audio, it just wasn’t what I would’ve done. So, I tried to focus on the positive of it being a good exercise in improving my sound design skills. If you can make a sound that sounds like what is in someone else’s head, then you have some awesome sound design skills!”

There is no right way to decode (or encode) feedback, but make sure you understand the direction a creative lead may want your revisions to take. Communication, examples, and technical descriptions are just a few ways we can turn a muddy mess into something intelligible.

Contractor deadlines

Contractor deadlines

Another area where external forces may affect our process is when dealing with– or being– a contractor. Often the pressures contractors face are compounded compared to a “normal” production team. They lack the communication of what’s going on in the team and often just work blindly throwing content over the fence or being several days behind on builds. Conversely, relying on contractors brings with it the risk of an additional set of deadlines, review processes, and communication that wraps the macro challenges of production into a microcosm of those same potential issues.

The common thread in the previous issues returns as Kenny Young was quick to point out, “communication is clearly super important here.” He, Rob Bridgett and Jason Kanter all mentioned those rare times when a contractor didn’t work out, or bugs or content changes came in after the contract was up, and they were left having to re-do the work. This is a compounded issue involving scheduling, deadlines and production, and the more areas we bring into the picture the greater the chance of things not running smoothly. Bridgett tries to schedule for those potential pitfalls and external issues by setting, “deadlines with a safety net of extra time, so… If content arrives a little late on their end, or if the person is slammed and trying to get the content over to me, we always have some extra time to fall back on.”

People’s work styles differ as well and it can really help knowing what you’re getting into when hiring a contractor. As Jaclyn Shumate noted, “I think this is where having longer-term relationships with external partners is beneficial. Knowing someone’s work-style can solve problems that exist, because then you can plan for it!” If you know someone provides great content, but may take a little longer to produce it, or they’re really popular/busy so they often have multiple projects in the works, you can “[build] in more time in [their] schedules, so that we [can] have the assets we needed in time for our lock-dates.”

But we can’t always hire people we have worked with before or who are known entities. Jason Kanter brought up an anecdote where he was working on a project with a lot of dialogue and managing a team of dialogue editors. He was “trying out new editors in hopes of expanding the team which eventually meant running across someone who may have been a talented sound designer but simply didn’t connect with the specifics of the task at hand. . . Thankfully I was able to maintain a team of four or five reliable and talented editors but when working on a project for an extended period of time with a team of freelancers you’re going to run into issues like when another gig pops up or, there’s a death in the family. In those cases when I couldn’t find anyone to fill in I had to simply pick up the slack and do the extra work myself.”

Contractors are often necessary for a small team to get content done in time, but managing external team members is at least as challenging as managing an in-house team and usually much more so due to the challenges of lacking constant face-to-face, one-on-one communication. Even when you may be in the same building or room, you’re dealing with a whole new set of quirks, skills, and idiosyncrasies and it can be an additional challenge to get these to mesh with your schedule or production style. Hiring people you know and trust is a great way to make this relationship gel, but finding new people who work well is also rewarding. When those fail, most of us need to be prepared to jump in and fix what’s broken along with every other fire we’re putting out at the time.

Schedule/Milestones

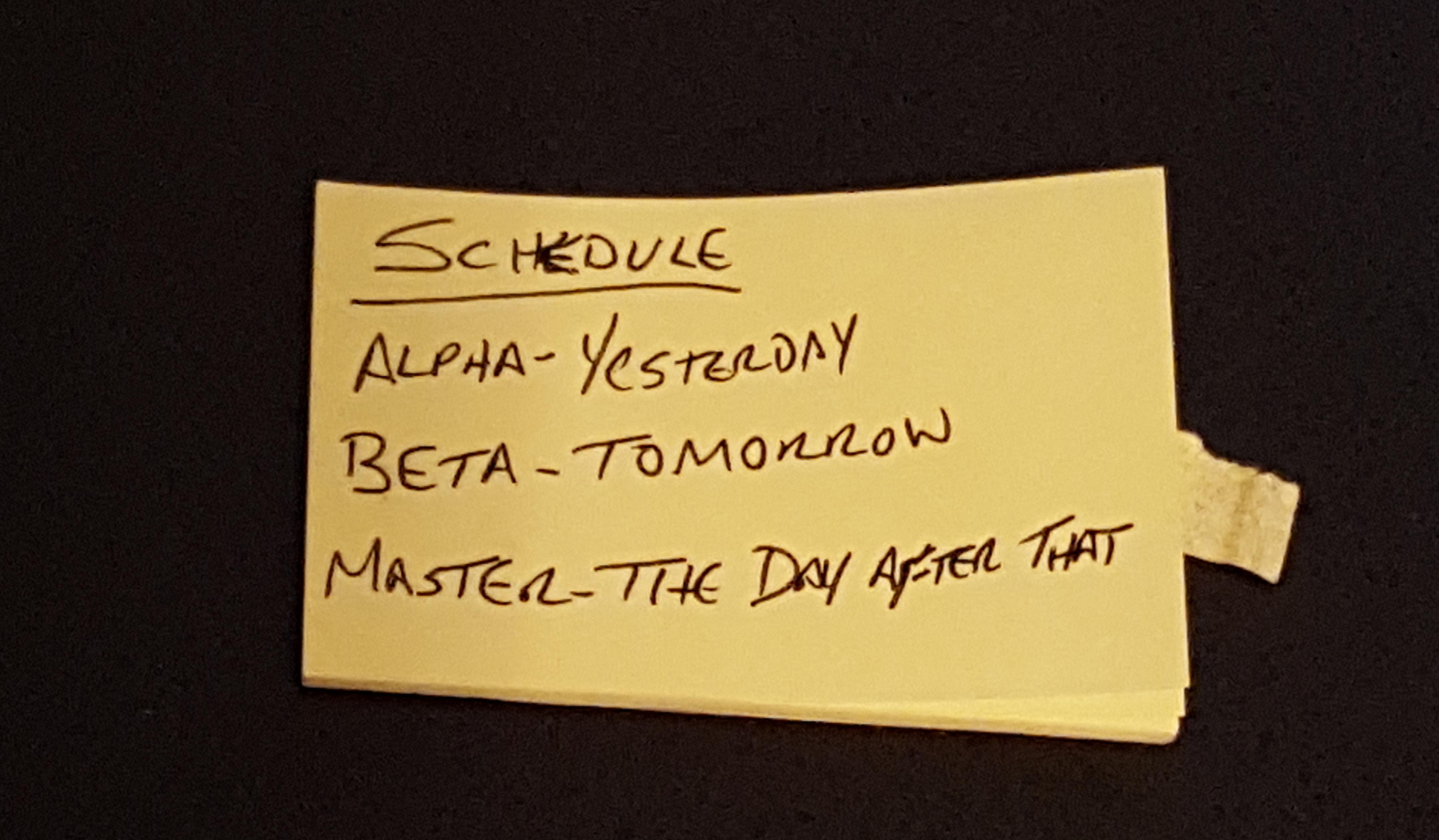

Without fail, a group of sound designers at a bar can commiserate on the classic misrepresentations of schedules and milestones. An alpha, beta, or any milestone means everyone is changing content without ample time for those of us downstream of all that work to react and respond to changes in any meaningful way.

Every interviewee acknowledged the challenges of needing to do critical work after all other disciplines. As Jaclyn Shumate noted, “every game I’ve been on has had some type of content dump or massive game re-structuring work right before ship. It’s the worst part of being dependent on other disciplines to complete your work.” Jason Kanter mirrored this sentiment in his own observation that, “there will always be 11th hour content dropped in our lap and we’ll be spending the last month of production working round the clock to wrap things up.”

And the (partial) solution is often to be proactive. Kenny Young suggests, “Get all your ducks in a row in pre-production so that you can execute like a ninja when you are shipping the game – this includes sucking up the knock-ons from new features.” Rob Bridgett will, “set expectations with the project planners, be clear about cutoff and delivery dates for other departments, agree on that plan and move forward. And when that plan falls apart, have a clear plan B ready with extra time specified for the audio side.” Similarly, Jaclyn Shumate will, “attack the issue from all sides. I prioritize, adjust, set, and communicate expectations, and then have conversations with the content creators and producers to see if there is anything we can do to lesson the load. After that it’s just digging in and do the best we can, and hoping that it won’t happen as bad again the next time around.” Sometimes if there is some extra budget around you can outsource some of the work, and that can be tremendously helpful. However, in my experience often by the end of the project the money well is dry…!”

As Shumate notes, sometimes we can reach out for help from contractors, when budgets allow, to try and fill in the gaps caused by the tidal wave of content changes as the end of a project. Jason Kanter has had success using other employees to help his teams out as well. While we often want to be touching the integration of our content to assure it is exactly as intended, as critical deadlines loom getting something close is better than having a bunch of missing sounds. A perfect example of this involves tagging animations. For a particular project for Kanter, after discussing the issues of late-breaking animations being added to the game, the “animators kindly agreed to take on the task of tagging animations for effects. This meant more work for the animators and less control by the FX creators but it’s the only way we could ensure that animations get tagged and that those tags get updated throughout production.”

Lastly we must also never forget that, while what we do is artistic, it is still commercial art. The schedule is the arbiter of how much time we should allot ourselves for various tasks. As Kenny Young reminds us, “don’t fall in to an overly ambitious workload or create self-indulgent technology or content solutions that are labour intensive in ignorance of what it takes to actually ship them, and everything else, to an insanely high quality level.”

Budget

Perhaps less of an issue than most of the others mentioned here, short of never having enough money to buy nice new equipment, budgetary issues are still often controlled externally of our department. We may request a budget and provide itemized breakdowns of spending and proposed person-hours of work, but there is almost always someone else telling us how much money they’re going to be giving us to get our job done. The challenge then is to make something great, even if the monetary figures don’t add up.

Obviously, the biggest potential issue with a budget is not having one. But it can be just as tricky to have a budget, and not know what it is! As Jason Kanter notes, “I can deal with budgetary restrictions but trying to determine what you can spend without being given a ballpark or even knowing the overall expected cost of the project is no fun. Eventually it just turns into overshooting in the dark based on what you want rather than what the project can handle.”

This is yet another place where communication can smooth a potentially sticky area. Jaclyn Shumate considers herself lucky because she’s never really faced any major hurdles involving budgets. For her, it’s been, “Not about getting big ones, but about getting clear ones and being able to stick to them.” By having her budgets communicated clearly to her, she is able to allot proper funds where they are needed without second-guessing or planning blindly. Rob Bridgett mirrors this sentiment when he says, “having [a] detailed audio budget broken down and agreed upon at the very beginning is absolutely the best approach, that way you can see exactly where you can move things from and to (foley, library sounds, mix etc), rather than just having a big pot of money assigned to ‘audio’ that looks big, but isn’t really!”

It helps to be flexible when possible with regards to budgets as well. Kenny Young has had, “zero budget on some projects, and I’ve been offered blank cheques by the publisher on others, but I’ve always worked as efficiently as possible.” For Rob Bridgett, he finds additional success by dealing with budgets, “openly and with an eye and ear on opportunity rather than digging heels in, because the opposite can also be the case when extra budget is floating around.”

The problems we all face daily in our jobs are quite common. We all deal with the frustrations of external forces putting pressure on our work – from communication and feedback to contractors and budgets. Often the way the successful sound designers above have worked through these issues is by being proactive in preparation, reactive in dealing with issues as soon as they arise, and communicating, communicating, and communicating some more. Hopefully you’ve learned something from the talented leads who gave their time here. If not at least you know we’re all in the same boat heading down that production river, trying to avoid the rocks.

Leave a Reply